“I Think I Am Doing the Right Thing, but I Meet with Such Stiff Resistance”: The Team behind China’s Anti-Overwork Campaign

On the night of October 28, Meng Weifeng found out that the public account and mini-program he and his teammates set up for their “WorkingTime” project, primarily made up of a spreadsheet recording the working hours in various industries throughout China, were taken down from Tencent’s popular instant messaging service WeChat, with no exact reason given as to why.

“The sudden removal of our mini-program and public account has led to a massive loss of traffic,” Meng said in a written response to Pandaily’s questions, declining to disclose his real name.

Without significant channels through which it could reach a wider public, the viral project that has amassed more than 10 million views in less than a week, has been reduced to a flameout amid a mixture of anti-overwork sentiment and digital censorship in Chinese society.

From “WorkerLivesMatter” to “WorkingTime”

Meng is among four college seniors who all had recently landed job offers at top Internet companies in China and decided to launch a project to make work schedules across the country’s different industries more transparent for jobseekers.

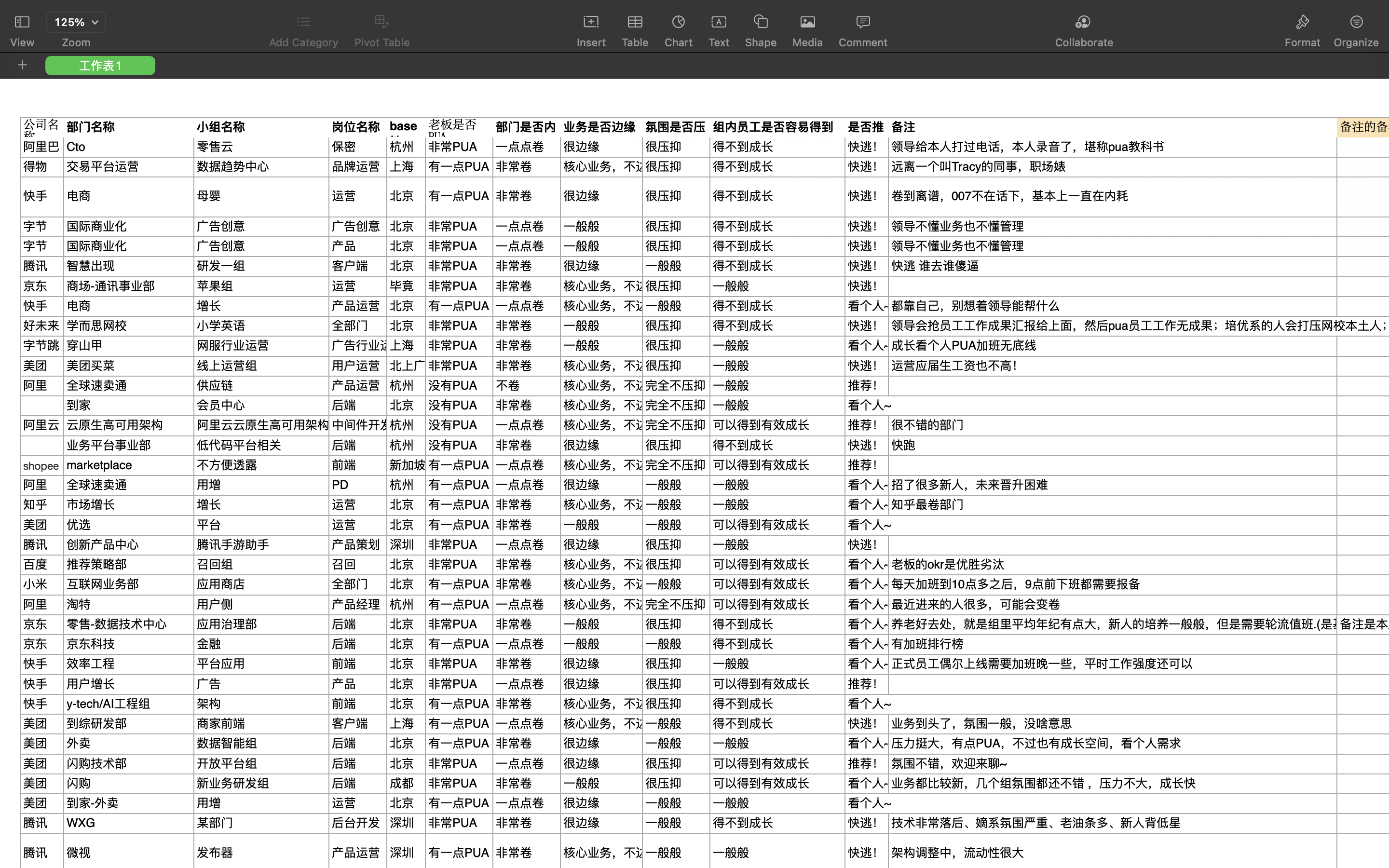

On October 8, the team started a spreadsheet dubbed “Company Schedules” on Tencent Docs, which allowed users to share their companies’ working hours by simply editing the document themselves. Details included the companies’ names, departments, positions, cities, schedules and other aspects of working conditions. On GitHub, a Microsoft-owned code sharing site which is used by millions of Chinese developers, the four young aspiring programmers created a repository for their project and gave it an even snappier name – “WorkerLivesMatter”.

“Workers also need to live!” declared the campaign’s GitHub page, referencing the long-standing work-life balance dilemma in the country. The campaign also corresponds to an online protest staged by a group of anonymous Chinese tech workers on GitHub in early 2019 titled “996.ICU”, meaning that the 996 work schedule common among the country’s tech industry – 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., six days a week – could send staffers to the intensive care unit.

Different from the 996.ICU campaign, Meng’s project was based on a shareable document which welcomed contributions from employees across a variety of sectors including tech, finance, retail and manufacturing. The project’s collaborative nature and ability to remain anonymous gave it a rebellious core which echoed the backlash against the excessive working culture in China and propelled its virality on social media. The spreadsheet had received 1,173 entries, as of 7 p.m., October 12, only a few days after it went online, according to a post written by one of the organizers under a related discussion on Zhihu, China’s Quora-like Q&A platform.

On October 13, the discussion ranked first on Zhihu’s trending list. A day later, one hashtag about the project went viral on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like microblogging service. Since Weibo has a user base of more than 573 million, the prominence of the hashtag marked the moment when Meng and his peers’ efforts broke into public view.

However, the great popularity brought with it great pressure.

One of Meng’s teammates told Pandaily that he had also submitted an entry detailing his experience of interning at a tech company. On October 15, he received a call from his former supervisor who recognized his identity from the information he had input into the spreadsheet. “He said to me via the phone that, ‘We are social animals and we need to know about social norms. Your behavior has shown disrespect to our team and you’d better mind what you say and do,’ ” he recalled. “After we hung up, I felt awful. My heart sank. I just don’t understand. I think I am doing the right thing, but I meet with such stiff resistance. Maybe my leader’s correct. I need to respect the social norms.”

Soon after the project came under the spotlight, Meng and his team changed the initiative’s name from “WorkerLivesMatter” to “WorkingTime”. “The former sounds like we’re gonna launch some social movement, which is actually not consistent with our intention,” Meng explained in a written reply. “Our statistics will be only used for public service to grant jobseekers the right to know, to choose and to negotiate. ”

The brutal work culture in China

As of the end of October, the WorkingTime spreadsheet contained more than 6,000 entries, which gave a glimpse into the draining working conditions at many Chinese companies.

For example, a staffer working at the live-streaming unit of TikTok owner ByteDance reported a “11-10-5” work schedule – 11 a.m. to 10 p.m., five days a week. An employee of Tencent Music Entertainment, the online music subsidiary of Tencent, reported a “10-11-5” schedule.

In recent years, news of incidents involving premature deaths of young white-collar workers in China have hit the headlines and provoked criticism against the culture of extremely long working hours. Last December, a 22-year-old woman working at Pinduoduo, one of China’s largest e-commerce platforms, died after staying at the office until 1:30 a.m. Earlier this week, a 36-year-old employee of Chinese automotive maker BYD was found dead in a rental house and police have ruled out criminal causes. According to his work records, throughout the month of October he had worked about 12 hours a day for 26 days for a total of about 280 hours.

Ryoma Cheng, an IT worker at a Guangzhou-based affiliate of a Chinese Internet titan, a company that has between 3,000 and 4,000 staff, participated in the WorkingTime campaign by submitting information about his work schedule via the link one of his colleagues forwarded to him. Cheng told Pandaily that he usually clocked in at 10 a.m. and clocked out at 10 p.m., occasionally working overtime until 5 a.m.

“I don’t have any choice but to quit,” said Cheng. The 27-year-old Chinese Communist Party member who believed in Marxism and Socialism expressed his support for the project, adding that it could not only help jobseekers evaluate their offers but also awaken workers to exploitative practices. Cheng said that he had already started looking for other jobs in the hope of maintaining a regular schedule.

As Chinese authorities have embarked on a regulatory crackdown on the country’s technology sector, the Big Tech companies’ overtime work culture has also come under heightened scrutiny.

In August, China’s Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security and the Supreme People’s Court released a collective memo of ten court decisions related to workplace overtime disputes, and said that the 996 work arrangement represents a serious violation of the law pertaining to maximum allowable work hours.

SEE ALSO: Top Chinese Governing Bodies Call ‘996’ Work Culture Illegal

A handful of Chinese Internet heavyweights have changed their work policies over the past few months. ByteDance and rival short-video platform Kuaishou cancelled the so-called ‘big week/small week’ policy requiring employees to work six days every two weeks earlier this year. In November, screenshots of an internal document issued by ByteDance spread online. The screenshot showed that the social media group orders its staffers to work from 10 a.m. to 7 p.m. on Mondays to Fridays, in compliance with China’s labor laws. But the situation is not crystal clear. A full-time ByteDance employee said in a recent interview with Pandaily that she and her colleagues haven’t received any formal announcement from the company, adding that they still stick to their previous work schedule.

It’s not the end… yet

According to a timeline posted on WorkingTime’s GitHub page, the lurking shadow of censorship has enveloped the project from start to finish. Access to its GitHub repository and official website hosted on Alibaba Cloud was blocked on browsers and messaging services offered by companies including Tencent, Baidu and even Alibaba itself. On October 19, the original spreadsheet on Tencent Docs became unaccessible and the related Zhihu discussion page also disappeared. After the project’s WeChat public account and mini-program were removed, Meng and his peers felt like they had reached a tipping point.

Shortly after their interview with Pandaily, the team announced that they decided to terminate the WorkingTime project. “We’re still walking our paths and the world is still spinning,” read the last note left by the group of young people on their GitHub page before it was deleted on November 5. “Thanks to all the people who have supported and paid attention to the project.” The link to the official website also went dead.

However, what offers a glimmer of hope is the fact that the short-lived project will not be the last effort made by the country’s burned-out workers to combat their gruelling working conditions. Screenshots of another collaborative spreadsheet circulated on Chinese social media sites earlier this week, crowdsourcing a blacklist of bad managers at major Chinese Internet companies and detailing workplace dynamics on different teams.

The momentum of digital, collaborative and grassroots campaigns in China seems to remain strong. Jiang Ying, a professor at China University of Labor Relations and a leading expert on China’s Labor Law, was quoted as saying in an article about the abusive 996 work schedule published on the People’s Daily, “When resorting to the legal system for protection, there is a price to pay: time, money and the risk of losing your job. And as a result they took to cyberspace.”