Countryside Feminism: an Intricate Stereotype of China’s Antagonistic Females

On Mother’s day, May 10, Papi Jiang (Papi酱), one of the most popular online influencers in China, posted a photo of her holding her newborn baby. “I used to think a lot of tasks in life were incredibly tiring,” wrote Papi, “but now I’ve come to realize that nothing is more tiring than being a mother. Happy Mother’s Day to all the mothers out there! We deserve it.”

With over 33 million followers on Weibo, Papi is widely known in China for her witty and humorous self-made videos. Since 2015, the Shanghai-born, Central Academy of Drama graduate has been performing monologues in her messy apartment, often imitating different characters in a satire tone and poking fun at everyday topics including entertainment news, dating, and family relationships. The sharp observation and skillful acting demonstrated in these videos have made Papi an icon in China’s community of comedians.

Like other internet influencers, in the past two years Papi has started to venture into the entertainment industry by appearing in domestic variety shows. These shows dive into the ordinary, everyday life of celebrities; in them Papi revealed her modern, independent, and liberal attitudes towards female choices and marriage. For instance, Papi once said that she and her husband would go separately to celebrate Chinese New Year with their own families (instead of going to the husband’s side as most Chinese couples do), and that she seldom visits her in-laws. These arrangements are considered unorthodox in China to say the least (we have to admit, even self-considered “liberal” women like us struggle with these social expectations a lot), and in a society filled with patriarchal traditions, Papi’s individualistic attitude was a breath of fresh air that appealed to many young female fans.

So this is Papi Jiang, a talented young woman who has made a successful life in the internet age. Although she never openly discussed the issue of feminism or claimed to be a feminist, in the public imagination, she was the closest to a female icon as could be in today’s Chinese society: opinionated enough yet not too aggressive. Living a self-earned wealthy life yet doesn’t appear to be materialistic. Independent. Smart. Knows what she wants. Happy with life.

But every story has a twist. In the eyes of a certain group of people, there’s a side of Papi’s life that has failed to meet their expectation: the fact that Papi chose to become a mom (she even openly celebrated Mother’s Day!), and, unforgivably, called her newborn “Junior Hu (小小胡)” in one of her recent videos, revealing that the baby has taken her husband’s surname.

On May 11, the day after Papi’s Mother’s Day post (which was nothing but sweet and sincere), “Papi’s son is taking the father’s surname” became a trending hashtag on Weibo. Under the hashtag, vocal haters called Papi a disgrace, a marriage donkey (婚驴), a hypocritical female slave (女强奴) and many other vulgar names. It appears that some people believed that the surname decision by Papi was a “slap on the public’s face”, and, even worse, a “betrayal to the progress of China’s feminism.” In their eyes, Papi’s independent character was simply a lie; even though she was clearly financially successful and independent, the fact that she chose to “sell to her husband”, and “enslaved herself into a patriarchal marriage” proved that she had been faking it all the way. These wild abuses soon became loud enough that the public began to pay attention, thanks to the countless hungry internet media outlets who have always been craving a sensational headline.

We almost thought it was an April Fool’s joke when we first saw Papi Jiang’s story. The entire discourse appeared simply too absurd to be taken seriously; how could such a small mole hill (a few extremists’ lousy opinion toward a celebrity’s personal matter) escalate into such a mountain of public drama? But just before we decided to move on with a laugh, a term that had repeatedly appeared in the many posts in defense of Papi caught our eyes. “Don’t take those stupid Countryside Feminists seriously!” one says, “Look at those Countryside Feminists throwing their punches again!” Another says. “Stupid Countryside Feminists, @#$@#%#T%$W!!” Almost everyone says.

“Countryside Feminism (田园女权) ” is a term that one frequently comes across on Chinese social media nowadays in almost every thread associated with gender rights or feminism like this one with Papi. Everyone, including the two of us, has used it on some occasion to describe a certain group of people in our imagination, yet we’ve never bothered to think seriously about who they are, and what the term truly means.

Thanks to this ironic story of Papi, we now want to explore Countryside Feminism a little more.

Type “Countryside Feminism” on Zhihu (China’s Quora with more social media features) , three questions pop up on the first page: “What is the definition of Countryside Feminism?” “What is the difference between Countryside Feminism and real feminism?”, and, “Are Countryside feminists really so powerful as they seem to be nowadays?”

It seems the public is just as confused about Countryside Feminists as we are.

About three years ago, the term “Countryside Feminism” was first picked up by Chinese netizens as an abbreviation for “Chinese Countryside Feminist Dogs (中华田园女权狗)”. Notice that the term has little association with the countryside itself but is closer to “Countryside Dog (土狗)”, a very Chinese term referring to wild dogs with unclear/mixed pefigree (“土”in Chinese has a very nuanced yet clear pejorative meaning, implying low taste and low class). At first, it was used to describe two kinds of females following the ideology of two popular influencers at the time, Ayawawa and Mimeng (咪蒙).

Ayawawa, the self-claimed best-selling author, “relationships expert ” and “love queen” (We wrote about her back in 2017) ran a popular business focused on one thing: teaching women ways to catch the most-fit (rich and good-looking) husbands. Packaged under some complicated-sounding theories and methodologies (Ayawawa claimed that she had an incredibly high IQ score hence excelled in logic), she advocated females to strictly follow the orthodoxies of a patriarchal society, dress in men-appealing outfits and adapt gentle personalities in order to inflate their value in the marriage market. “Men and women are born different,” wrote Ayawawa in her book The Secrets of Perfect Relationships, “as women, all we have to do is to stay disciplined, contain our emotions, and leverage our sexual advantages. Don’t be a tough women, be a tender one.”

Ayawawa’s theory was nothing exciting other than the same old patriarchy cliche, but as an entrepreneur, she knew how to market her brand as sexy and fresh towards the many young Chinese women who were undereducated about gender rights yet were desperate to find a husband. As the business grew quickly over a few years, Ayawawa and her fans also became increasingly vocal on Chinese social media, promoting their theories and often caught in fights with feminists and the general public.

In May 2018, Ayawawa’s Weibo account was banned due to “inappropriate political speeches” as people found out she once claimed that “comfort-women” during WW2 had “gender advantage” compared to men. By that time, public disgust toward her and her followers was so high that people cheered for her ban. Ayawawa has since disappeared from the public eye.

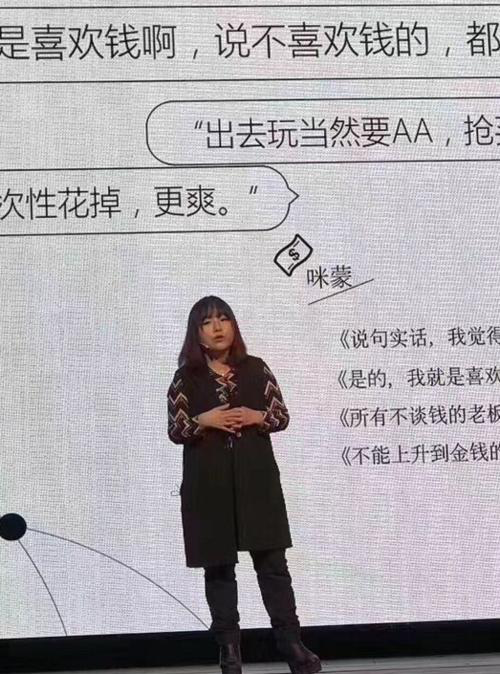

At the height of Ayawawa’s fame, another female influencer Mimeng (咪蒙), or, China’s “self-media” queen, was also enjoying the time of her life. A journalist-turned-businesswoman, Mimeng launched her own WeChat-based media brand in 2016 and attracted over 5 million followers within two years. The type of content Mimeng and her team produced, which was considered “psychic poison” by a lot of people, would always follow the same narrative: telling the stories of some women being dumped or cheated on by their partners, then transformed into “Alpha Females” that are “independent”and “strong.” In reality, these stories only reflected a materialization of both men and women and a hypercritical call for female rights based on the abuse of the other sex.

The more melodramatic Mimeng’s stories were, the more clicks they received and more income was generated for her company. In 2018, the regular price for advertising on Mimeng’s WeChat Official Account was reported to be 800,000 RMB, the top rate in China. Mimeng’s media business expanded furiously until one of her articles was reported (举报) by netizens in early 2019, resulting in a sudden ban of all of the media accounts under her name.

Mimeng and Ayawawa considered themselves to be completely different with each other. On more than one occasion, Mimeng openly called Ayawawa cancerous and sickening, while Ayawawa also expressed her dislike towards Mimeng in an internet-famous interview. As much as they claimed their own superior distinctiveness however, in the public eye, they were both capped under the same umbrella: Countryside Feminists. The online conversations were never about what the term truly means; all that matters to angry netizens (which is everyone nowadays) is that there was a term readily available to describe those who they didn’t like, specifically, the many loud and “extreme-sounding” women who appeared to threaten the social status of men in a traditionally patriarchal society. In a time when gender issues are becoming increasingly prominent, “Countryside Feminist” rose as a label large enough to fit any “angry women” without triggering any constructive conversations about the reasons for their angers, let alone on what feminism really means in today’s China.

The same empty generalization happened again in Papi’s incident. Those who stoked attacks on her motherhood were not Ayawawa or Mimeng’s fans, but a group of females with a more aggressive ideology: a complete hatred toward patriarchy and traditional marriage. Despite their group’s relatively small size (a top influencer in this group “写字楼大妈” currently has 280,000 followers on Weibo), they are extremely fierce and ever-ready to rain vulgar verbal abuse on those who show even the slightest sign of being a “patriarchy supporter.” In their language system, males are called by the joint name “tripod (鼎)”, a mocking term to indicate that men have no value other than for reproduction. Women who choose to step into traditional two-sex marriages like Papi became “marriage donkey (婚驴)”, and once a girl is married, her whole family becomes “donkeys” — enslaved animals. (“一人嫁女, 全家做驴”).

In a society where basic female rights are still ill-protected, these discontented female voices are becoming increasingly loud yet have so little space to be placed. The more vocal these females are, the more they fit into the stereotype of nasty “Countryside Feminist”, and the more they are alienated. “True feminists” don’t consider them to be part of the group, and the general public sees them as a joke, or, even worse, simply representing feminists in general. The result? More stigmatization, more segregation and more disappointment.

Last weekend, the two of us attended an online seminar held by Lü Pin, a journalist and a pioneering feminist activist who currently resides in New York. (The seminar was somewhat mysterious as we only came to know about it from a poster shared by a feminist friend, and during the 3-hour Zoom call, signals were constantly disrupted for unknown reasons.) Lü and her activist friends discussed the journey of the feminism movement in China in relation to social media, in particular, how online discourse such as “Countryside Feminism” could be dangerous because it could divide those who aim to push the movement forward. “The stigmatization of feminism has started to rise rapidly in China,” Lü cautioned the over 500 online attendees at the end of the seminar, “We must stay extra cautious and be more united to fight for the true cause of feminism.”

The same evening, I casually browsed Kuaishou, the short-video app that is particularly popular in China’s lower-tier cities and countryside. A few swipes led me to the page of “Boxing Bro (散打哥)”, thetop influencer on the platform with 50.8 million followers. In one of his most trending videos titled “brotherhood”, there was a scene of him slapping his wife so hard that she collapsed on the sofa for “being impolite to the brothers.” The video has received over 460,000 likes so far.

This is the reality we are coping with today. The internet has made human connections so easy that we are able to immerse ourselves in two completely different scenarios – a scholarly feminism seminar and a popular short-video drama involving domestic violence – within a few touches on our digital device. Yet the internet has also made us so far apart, trapping every one of us in our own echo chamber, depleting our energy and capability to understand one another and ourselves. The story of “Countryside Feminist”, if nothing, reminds us of something valuable in a time that the middle ground for meaningful conversations are disappearing: always look beneath the label, and stay curious about people.